Anti-caste activist: Bhim Army chief Chandrashekhar Azad Ravan at a protest against the alleged gang rape of a Dalit girl, New Delhi, October 2020. EPA-EFE/ Rajat Gupta

“What is your full name?” This question – when asked of an Indian – is often intended to determine the respondent’s caste. In a society where rigid hierarchies run deep, the answer to an innocuous question can hold the key to many doors – especially when it comes to employment.

Naming conventions in India are marked by explicit connotations of caste lineage and at times, even the intricate details of subcategories within a caste group too. Today, names are typically shorter, with a first name and a surname that connotes the caste group to which the person belongs.

A draft report commissioned by the Indian Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment recommends that last names revealing the caste, religious, or cultural backgrounds of candidates should be kept hidden during recruitment processes.

Prepared by the Dalit Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DICCI) – an organisation dedicated to fighting caste oppression by fostering entrepreneurship and provision of capital among dalits (who sit at the bottom of the caste ranking) – the report recommends this strategy for both written exams and personal interviews across all levels of recruitment in the public sector.

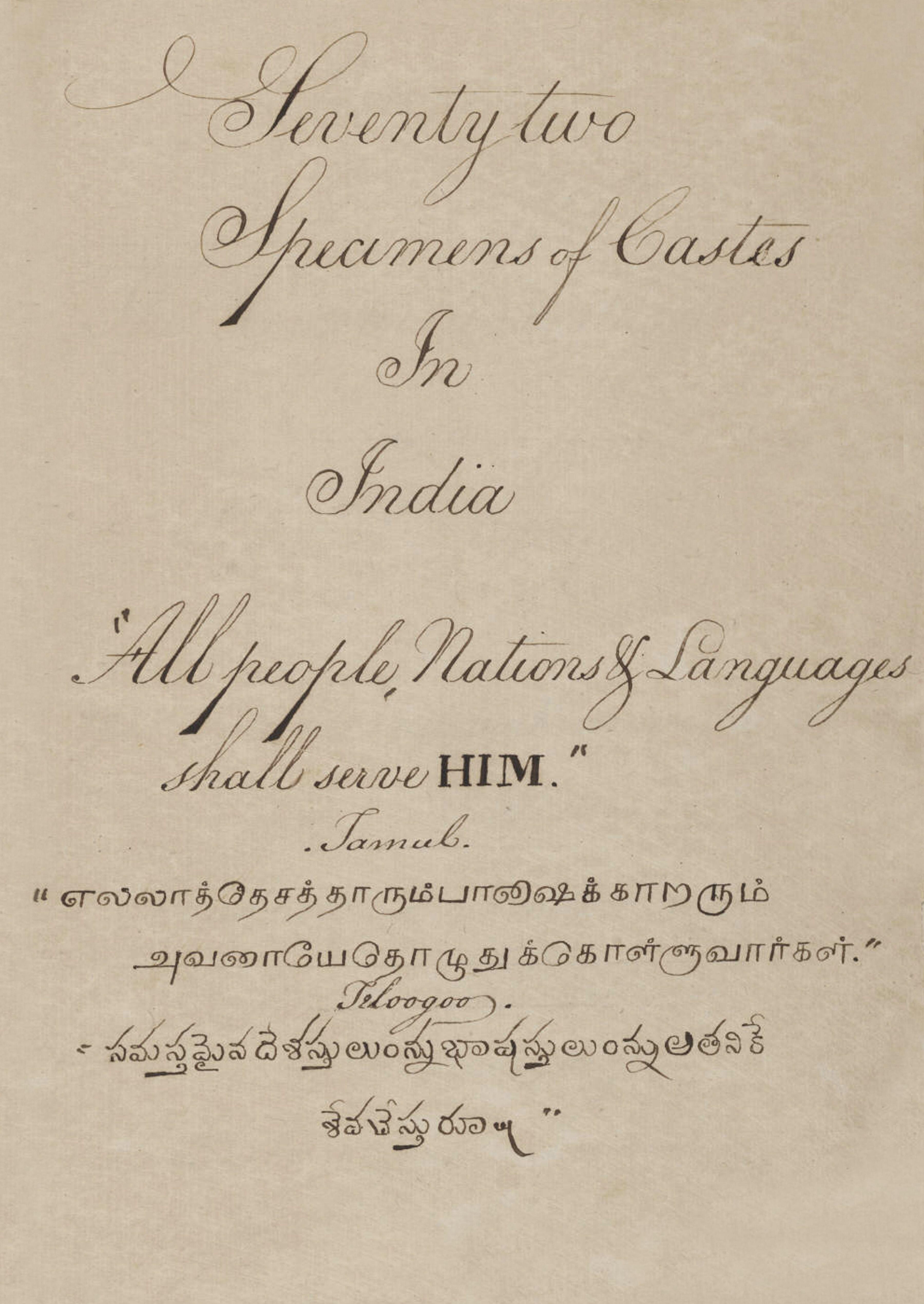

This needs to be seen in the larger context of the everyday caste-ism that is pervasive in India. The caste system is believed to have been codified in the revered Hindu codebook, the Manusmiriti. Revolving around the notions of purity and pollution, the Hindu society is divided into four groups, the priestly class, the warrior class, the merchant class and the servile class. The Dalits, formerly “untouchables”, are placed outside the system.

Everyone has their place: India’s entrenched caste system. CPA Media Pte Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Across centuries, the system has evolved into a complex matrix, with tens of thousands of sub-divisions. However, the defining element of the system – the legitimisation of differential treatment to people based on birth – is still intact. Iconic Indian jurist, politician and social reformer Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar noted that the caste hierarchy is marked by ascending order of reverence and descending order of contempt. Today, the caste system plays a crucial role in determining a person’s access to opportunities, skills and resources.

Leaving aside its logistical challenges, how far can the strategy of anonymous recruitment go to address centuries of exclusion? The draft report argues that:

In the absence of such direct information, social background of candidates is guessed to a great extent from the names like the Nayer, lyer, Iyengar, Naidu, Menon, Bandhopadhyaya, Chathurvedi, Gupta, Patel, Panda, etc.

Interestingly, these common Indian surnames indicate not only the caste position of their bearers but also their regional identity. For instance a person with the surname “Rajput” in northern India, where the said caste is numerically and socially dominant, would signify more social power compared to a person with the same surname in the south.

The surname “Bandhopadhyaya” – often spelled in its anglicised version as “Banerjee” or variations thereof – is an “upper-caste” Bengali Brahmin surname. This fact is common knowledge – and few Indians would fail to identify it as such. But not all Bengali surnames are as easily deciphered. For instance the last name “Sarkar” or its variations are often referred to as a title rather than a surname, because it has been bestowed on individuals under the Mughal regime. Today this last name is used by individuals across caste and religious categories.

Rejecting caste-based naming practices and adopting generic or symbolic last names has been a longstanding strategy within the anti-caste movement across the country.

What’s in a name?

Across India, last names describing caste-based occupations have commonly been used as slurs to humiliate Dalit or Bahujan individuals, thereby reinforcing caste-based hierarchy and ostracisation. Since the mass political mobilisation of these groups in the 1940s in the south by the Dravidian Movement and the 1980s and 1990s in the north by the Lohiaites, many have discarded their caste surnames and now use a second first name instead.

Chandrashekhar Azad Ravan, leader of the Bhim Army and Azad Samaj Party, has been featured in the Time list of 100 emerging leaders.

Born into a Dalit community, he has adopted the two names Azad (meaning free) and Ravan. Ravan is a mythical figure presented as a villain in conventional North Indian renditions of the Hindu epic Ramayan, which celebrates the victory of Ram, an “upper-caste” king. This choice of names displays a potent mix of assertion and subversion.

Appeals to discard caste-based last names have been extended to and accepted by dominant caste individuals as well. This is of course a double-edged sword. Discarding the caste name alone does not undo social power accumulated over centuries and may in fact serve to mask it.

Caste in the civil service

Affirmative action policies have been in place in public-sector recruitment since the early 20th century. This has involved a stipulated representation of marginalised caste groups such as the Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs) and Other Backward Classes (OBCs). All of these groups are deemed to have historically been denied social, economic and educational progress.

But data shows that the allotted quotas have never been filled. For instance, in Class A, or high-ranked posts, as of 2015, 13.3% were SCs – fewer than the quota of 15% that had been required since the affirmative action reforms in 1950s. Meanwhile, as of 2013, 8.37% were OBCs as against the stipulated quota of 27% since the 1990s, when the quotas were implemented.

The quota system only provides for entry-level representation. In practice, “lower-caste” groups achieve close to zero representation in senior civil service roles. For instance, as of March 2011, there were no SC secretaries and only four ST secretaries out of 149 in the whole civil service. In 2019, the number remained dismal with one SC, three STs and zero OBCs in the 89 secretary-level posts.

Social engineering

Recent modifications to the implementation of some quotas have shifted the focus from the representation of marginalised groups to merely addressing the economic weakness. The new criterion prioritises a temporary condition which is assessed using annual income and wealth rather than a more entrenched social reality, which is social and educational deprivation. Policies that have foregrounded individual rights over community representation further aggravate the picture by shrinking the number of “lower castes” entering the bureaucracy.

To make matters worse, the vitriolic opposition to affirmative action by many “upper-caste” groups has tilted public discourse against the struggles for caste justice. Against this dire backdrop, how far can the proposed recruitment reforms go?

While “blind” recruiting can surely work against existing caste prejudice, such a measure is insufficient when it comes to reforming the structural dimension of caste power. Names alone are not the repositories of caste privilege. Skin tone, accent, fluency in English, familiarity with pop-culture references, and food habits are some of the prominent proxies through which caste is commonly gauged in an unspoken fashion.

With significant structural barriers to education and equal opportunity, everything from the school or college one attended to the candidates’ internship experience and hobbies can be read as proxies for caste status. The set of candidates who can afford to participate in the civil service recruitment process constitutes a small, rarefied pool. Within this the proposed measures can extend the possibility of equal opportunity. But in the bigger picture, it will remain a drop in the ocean.

Srilata Sircar, Lecturer in Indian and Global Affairs, King’s College London and Vignesh Rajahmani, PhD researcher in the India Institute, King’s College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.